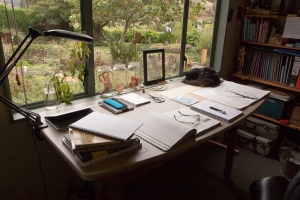

Chapter review from Book on Mark Dion Dion M. Mark Dion (1997) London, Great Britain. Phaidon Press Ltd I had been confronted by Mark Dion’s work before and dismissed it as not having any relevance to my own practice. As I had looked at his piles of rubbish, or the orderly arranged china chards, the animals hanging from a tree and simply did not get it. Now I realize that what I actually did not get was, doing some back ground reading on these works, the thinking behind them, the reasoning of these seemingly random or unattractive piles of stuff. Now that I have bothered to read the chapter Survey - A Natural History of Wonder and a Wonderful History of ‘Nature’ by Lisa Graziose Corrin from the book Mark Dion, I have changed my mind. Actually it has opened my mind to his work and now find it very clever, very informative and very interestingly close to my own practice. How silly I now feel to have dismissed his work. Now that I am over that, I want to share some of the main ideas and thoughts that struck me from this chapter that resonated with me and have helped me to understand how to present my own work to give the viewer an experience, that relates to how I feel when I create my work (also getting a shove from my studio supervisor has helped me go beyond my comfort zone). This chapter made me realize that I as a gardener am a collector (my garden and plants are what influence my practice), a very selective collector, must be added. Since I am researching the relationships between people and plants for my Arts Masters, this very odd relationship needed further exploration. As initially I felt like a botanical explorer, ‘discovering’ and documenting plants, but I concluded that really first and foremost, I am a plant collector. So this reading actually helped me pull my practice/ideas/work together at this point. A plant collecting starts like any collector with first looking for the ‘right’ specimen. After a desirable specimen is located, I then ‘display’ these ‘discoveries’ often according to some organized or strict rule. Placing of the plants in the garden is like cataloging them, as they will often be placed next to other plants for a reason.(such as companion planting, colours complement and the lost goes on). Once planted they are then lovingly maintained, fed and watered to ensure survival and long term enjoyment though each of the seasonal changes. This ‘discovery’ through this chapter had made me research and think about this collecting behaviour: Collecting by human’s has been an obsession for centuries. As human’s we collect, pick up things that amuse, amaze, intrigue, challenge, complete.........us, and many more reasons. These collections were first displayed in a Cabinet of Curiosities or also called the Wunderkammer, during the 14th to about the 18th Century These places displayed an encyclopedic collection of curiosities that had been brought back from distant places. The items on display were objects that had not been categorized or classified at that time in history. (Much of Dion’s work comments on this earlier collection and also the subsequent separation into ‘appropriate’ groupings as per the now common museum style) The purpose of these displays was often to show explorations done, power, prestige, a place for contemplation and wealth, amongst other things. The bringing back the booty from far away places appeared to be also a way of taming the chaos of the unclassified and newly discovered world (Dion pg 54). The inventory of a typical Wunderkammer contained at least one from the following groups: Naturalia - these were specimens created by God, such as animals, vegetable or minerals (stones etc) and also unique examples of nature that were odd or deformed. Artificialia - these were things made by man such as paintings, sculptures and hybrid combinations of natural elements perfected by man, eg a shell set on a mount Antiquitates - these were objects of historical significance, such as medals of rulers. Ethnographica - items that had an exotic association with Native people from the New world. (Dion pg 52) “These objects were displayed on shelves, set in niches, hang from the ceiling and were seen as a holistic group of objects that could be touched, re-arranged poetically to produce a kind of awe that could enlighten the mind, delight the senses & encourage conversation”. (Dion pg 52) It is interesting to note that the objects were arranged according to taste and visual appeal by the owner, and no thought was given to their function, origin, historic relevance. While reading this I looked around my own studio and realized that I was sitting in my own Wunderkammer, as on my desk was a dried leaf, a couple of sea urchin casings, a piece of glass from the beach; beaten and rounded, 2 botanical screen prints on glass, 3 preserving jars with foliage in them, plant books and my cat. How could I before reading this not have realized I am a naturalist, a botanist, an ethnobotanist, collector and a gardener all at the same time.  My studio table as a Wunderkammer. This collection on my desk was not ordered or systemized, but they were simply items from nature that had got my attention, because they were variable or novel in some way - a contemporary Wunderkammer. One work by Dion that comments on classification is his Scala Natura (1994). ‘This work was a direct subversion of Aristotle’s attempts to classify life according to a hierarchical system’ (Dion pg 71). This work makes you wonder if such a classification could be true or even possible, but then you wonder why a wheel has more importance than a gourd, or is the philosopher’s head, which sits at the top, the most important and the wheel at the base least? The Era of Enlightenment brought an end to these Wunderkammer’s. As the Wunderkammer came under threat and ended “With the development of Linnaeus Taxonomy, this endless play within the Wunderkammer was superseded by a rational structure that would govern display methods of modern museums” (Dion pg 53). As collections now became divided according to their classification/grouping. Each group ended up with it’s own display language, where minerals and fossils were laid out behind glass walls on glass shelves with labels, paintings were hung on the wall and book were moved to the library. Gone was the ability to touch and move items around, play with them and learn their feel. (As an aside: Also gone was the extra ordinary appeal of many of these items, as they went from being seen by only a few to being accessible to many. What is interesting to note here is that it appears that now we can see any species at any time in any countries museum, This easy access has created a problem now of things beings less valued, less understood that they maybe endangered (Dion pg 84). This is certainly very relevant for many mammals, none the less it is also impacting on plant life.) This change of display also changed the way information and knowledge was shared, as now it was through verbal rather than visual & physical that learning was done. (Dion pg 53). With the Wunderkammer there were infinite series of discoveries to be made and with an open mind you could go on an adventurous journey. (Dion pg 79) This display method allowed the viewer to see many ‘unrelated’ items and make their own interpretations and narratives, as there was no strict museum structure in place. (Dion pg 79) This is a very interesting concept in relation to my gardening/arts practice, as gardening knowledge you used to learn from your parent/grandparents, mostly by working alongside them, by being part of the planting and harvesting. Much of my learning has been done through trial and error or reading books, because my family (my father is an avid gardener) live in the northern hemisphere. So my own learning has been through the verbal, not the visual/physical. With many failed crops, ornamental plantings, not helped by shifting around NZ and having to learn the different climates. What is interesting to note is that my garden style & plant collecting is very much a blend of 2 worlds. Much of Dion’s work is about trying to remove the artist as the main focus of the work and blur the lines between art & pedagogy. Combining different professions to create work and often comment on the narrow attitudes art, knowledge and culture within the museum display methods. As the function now of a museum curator are to locate, acquire, organize, catalogue, display, store and maintain collections of related items. What is an interesting point to ponder is ‘when you collect & remove a natural element from one context to another, then is this element/specimen and the subsequent observation still true and natural? Animals show different behaviour patterns in captivity than in the wild, plants do to, but this change is much more subtle. And is collecting something from my own garden just a serious as something from a far flung or ‘romantic’ jungle? (Dion pg 70) My thoughts on this were initially no, but after reading and researching I do belief it is just as serious. As the observations you gain from plant ‘behaviour’ in a garden are valid within the context of a garden, they are not valid conclusions of that plants behaviour in the wild. I concluded that: As a plant collector I make similar decisions as any other collectors, as I have plants that are ‘special’ and I only have one of them, they will have pride of place and will be ‘supported’ by other plants that are less special, but important all the same. Some plants I place with great intentions, while others simply arrive or make themselves known unintentionally. As a plant collector I am a botanist & a naturalist (even though I get into my car to go to the garden centre, the only danger I may face are other drivers on the road); I am an ethnobotanist, as I choose plants that will nourish or heal or even discard some and I have an obsession, of which I am proud.

My studio table as a Wunderkammer. This collection on my desk was not ordered or systemized, but they were simply items from nature that had got my attention, because they were variable or novel in some way - a contemporary Wunderkammer. One work by Dion that comments on classification is his Scala Natura (1994). ‘This work was a direct subversion of Aristotle’s attempts to classify life according to a hierarchical system’ (Dion pg 71). This work makes you wonder if such a classification could be true or even possible, but then you wonder why a wheel has more importance than a gourd, or is the philosopher’s head, which sits at the top, the most important and the wheel at the base least? The Era of Enlightenment brought an end to these Wunderkammer’s. As the Wunderkammer came under threat and ended “With the development of Linnaeus Taxonomy, this endless play within the Wunderkammer was superseded by a rational structure that would govern display methods of modern museums” (Dion pg 53). As collections now became divided according to their classification/grouping. Each group ended up with it’s own display language, where minerals and fossils were laid out behind glass walls on glass shelves with labels, paintings were hung on the wall and book were moved to the library. Gone was the ability to touch and move items around, play with them and learn their feel. (As an aside: Also gone was the extra ordinary appeal of many of these items, as they went from being seen by only a few to being accessible to many. What is interesting to note here is that it appears that now we can see any species at any time in any countries museum, This easy access has created a problem now of things beings less valued, less understood that they maybe endangered (Dion pg 84). This is certainly very relevant for many mammals, none the less it is also impacting on plant life.) This change of display also changed the way information and knowledge was shared, as now it was through verbal rather than visual & physical that learning was done. (Dion pg 53). With the Wunderkammer there were infinite series of discoveries to be made and with an open mind you could go on an adventurous journey. (Dion pg 79) This display method allowed the viewer to see many ‘unrelated’ items and make their own interpretations and narratives, as there was no strict museum structure in place. (Dion pg 79) This is a very interesting concept in relation to my gardening/arts practice, as gardening knowledge you used to learn from your parent/grandparents, mostly by working alongside them, by being part of the planting and harvesting. Much of my learning has been done through trial and error or reading books, because my family (my father is an avid gardener) live in the northern hemisphere. So my own learning has been through the verbal, not the visual/physical. With many failed crops, ornamental plantings, not helped by shifting around NZ and having to learn the different climates. What is interesting to note is that my garden style & plant collecting is very much a blend of 2 worlds. Much of Dion’s work is about trying to remove the artist as the main focus of the work and blur the lines between art & pedagogy. Combining different professions to create work and often comment on the narrow attitudes art, knowledge and culture within the museum display methods. As the function now of a museum curator are to locate, acquire, organize, catalogue, display, store and maintain collections of related items. What is an interesting point to ponder is ‘when you collect & remove a natural element from one context to another, then is this element/specimen and the subsequent observation still true and natural? Animals show different behaviour patterns in captivity than in the wild, plants do to, but this change is much more subtle. And is collecting something from my own garden just a serious as something from a far flung or ‘romantic’ jungle? (Dion pg 70) My thoughts on this were initially no, but after reading and researching I do belief it is just as serious. As the observations you gain from plant ‘behaviour’ in a garden are valid within the context of a garden, they are not valid conclusions of that plants behaviour in the wild. I concluded that: As a plant collector I make similar decisions as any other collectors, as I have plants that are ‘special’ and I only have one of them, they will have pride of place and will be ‘supported’ by other plants that are less special, but important all the same. Some plants I place with great intentions, while others simply arrive or make themselves known unintentionally. As a plant collector I am a botanist & a naturalist (even though I get into my car to go to the garden centre, the only danger I may face are other drivers on the road); I am an ethnobotanist, as I choose plants that will nourish or heal or even discard some and I have an obsession, of which I am proud.

comments powered by Disqus